“We don’t make programmes about ordinary people – we make programmes about remarkable people who don’t happen to be famous”

(Alastair Wilson, BBC Manchester)

Denis Mitchell, c. 1957 (courtesy of Betty Mitchell)

Last Thursday (09/07/15) was quite a red letter day for me, as the BBC Radio 4 broadcast a half-hour tribute to a hero of mine, the innovative and influential but sadly neglected documentary pioneer Denis Mitchell.

The filmmaker Michael Darlow, who worked with Mitchell at both ATV and Granada, believes that ‘it is a measure of the continuing low esteem in which television is held as an art form’ that there are so few sustained assessments of Mitchell’s remarkable body of work:

Had he made his films for the cinema it is a fair bet that the true successor of John Grierson and Humphrey Jennings would, in a career spanning more than thirty years and one hundred programmes, have had numerous books and analytical articles devoted to him. (Darlow 1990)

And perhaps it can be said that radio is placed even lower in the cultural hierarchy, so that Mitchell’s pioneering work in that medium has hitherto been more or less forgotten, or at least obscured by the long shadow cast by his award-winning documentary films. That is why I’ve subtitled this post ‘Seen But Seldom Heard’.

There have been several television profiles of Mitchell (one made by Darlow for ITV’s Aquarius arts programme in 1970 and one made by the BBC following Mitchell’s death in 1990). Darlow’s in particular is excellent and revealing, but neither of these explored his radio work in any detail whatsoever. So it was pleasing to not only hear people like Ken Loach, Kevin Macdonald, Gillian Reynolds and Mary McMurray (Denis’ researcher at Granada Television, and clearly someone who has a deep understanding of his significance) discuss Mitchell’s use of sound, but also to hear many extracts from Mitchell’s People Talking radio series throughout. This series was Mitchell’s purest expression of his love for the vox populi (‘I’d fallen in love with the human voice’ he would say in interviews), and his commitment to documenting the extraordinary lives and impressions of what are repeatedly and fallaciously termed ‘ordinary people’.

The programme was edited quite skilfully to showcase the most remarkable moments in Mitchell’s radio programmes, although of course this meant that a sense of his exploration of a theme or slice of life in an individual programme was lost. So, for example, in 1955’s Night in the City (more on this programme later), Mitchell captured the nightly rituals (nuns praying, people working in the sewer, a tramp walking in order to keep warm) that go unnoticed or ignored because they are hidden from view, or because they are utterly taken for granted. Those unique voices Mitchell recorded often acted as a continual backdrop in the profile, rather than being ‘centre stage’, and the eerie nighttime silences that so effectively interspersed the voices were removed. But this is undoubtedly symptomatic of the considerable difficulties of outlining the shape of a wildly prolific and varied four-decade career in British radio and television into a 30-minute programme!

These extracts, however, did give a sense of how his work is, by turns, evocative, humane, yearning, raw, magical, vivid, perplexing, hilarious, bleak and surreal; or sometimes all of these adjectives at the same time. This was due to the incredible candour – and frequent bloody-mindedness – of his interviewees, and the sheer poetry of their vernacular speech. But it was also due to Mitchell’s unique understanding of people’s flaws and their hidden depths, and his artistry in editing and juxtaposing thoughts, reflections and epigrams.

I would, however, like to make a number of observations about Mitchell which the programme did not really convey, at least fully. These will allow me to showcase some of my archival research on Mitchell, and, more importantly, hopefully this post will hopefully serve to underline how unconventional his early work was, especially for the 1950s, and how it does not fit into any easy categories. In my opinion Mitchell was the greatest artist ever to have worked in British broadcasting, and it is unfortunate that he has frequently been overlooked in popular and academic histories of the media.

- Mitchell was not political but he was a non-conformist – he was fascinated by strange and arcane people and philosophies.

This is absolutely fundamental to Mitchell’s personality and career, and is something that was not just a passing phase or affectation, but something that speaks to a passionate inner belief in non-conformism. The earliest indication of this was in 1954, when Mitchell was a BBC features producer at the BBC North Region, and made a programme for the People Talking series entitled ‘Flying Saucers’, which was broadcast on the Light Programme on 20th May 1954. Unfortunately, only tantalising interview excerpts survive – not the finished programme. The following year he made a programme for the same series called ‘Unusual Beliefs’, which featured Violet Van der Elst (1882-1966), a psychic and renowned campaigner against the death penalty; Austin Osman Spare (1886-1956), an occultist and talented artist who had no ambition to sell his works; Cecil Hugh Williamson (1909-1999), Britain’s leading expert on witchcraft; and Egerton Sykes (1894-1983), explorer, archaeologist and ‘Atlantologist’. Mitchell also made a recording trip to the Isle of Man, where he documented an ancient belief which was still retained by an element of the community that myrrh is lucky, and that it bursts into bloom during the hours of darkness on old Christmas Eve. Again, the programme has unfortunately not survived, aside from this remarkable Isle of Man interview.

It can be said that cults, cranks and crazies feature in several of Mitchell’s radio and television programmes during this period; today this seems remarkable for a period in British history that is characterised by austerity and conformism. It is, however, important to emphasise that Mitchell’s interest in eccentrics was not exploitative; he was keen to capture the experiences of those ‘out of step’ with society rather than patronise or condemn them, which was also true of his genuine interest in tramps, prisoners and homeless people.

Incidentally, Mitchell’s interest in these areas slightly preceded that of Dan Farson, who, in the late 1950s, made series for ITV like Out of Step and People in Trouble about unconventional ideas like nudism, UFOs, witchcraft and Spiritualism.

- Mitchell was a pioneer of both psychogeography and sound art

Mitchell liked to walk around Manchester at night with his tape recorder, and often spoke (indeed he does in an archive clip from the recent BBC programme) about how he would sit in bomb sites during this post-war period, and would wait until people ‘came out of the shadows’ to speak to him. He would then befriend them, recording the conversation as it unfolded. This anticipated the approach to recording which would be used decades later by the sound artist Hildergard Westerkamp in the regular programme Soundwalking, broadcast on community radio station Vancouver Co-operative Radio in the mid to late 1970s:

I developed an interesting, fairly passive style of recording. I would just stand someplace and record. Then people would approach me. I got some very interesting conversation. I found the tape recorder a way of accessing this landscape… (quoted in McCartney 1995).

Mitchell combined a passive approach to recording with an active approach to editing – through his skill in gathering and editing actuality and ambience we as an audience attain the ‘strong pervading sense of a single sensibility responding to widely diverse materials’ (Reisz 1959: 52), to quote Karel Reisz, who wrote a perspicacious article on Mitchell’s work, which he greatly admired. Listening to Mitchell’s masterful 1955 programme Night in the City, it is difficult not to share his infectious sense of wonder and mystery at the city at night and its unique soundscapes. This sense of wonder, which is concomitant with Mitchell’s ability to make the everyday miraculous, can at least partly be attributed to the fact that, after returning to Britain from South Africa, he saw everything afresh. This was pointed out to me by Linda Mitchell, who explained that Denis had made recordings predominantly in agricultural areas when he had worked for the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) in the 1940s.

In exploring Manchester at night, Mitchell shared a great deal with the many English writers featured in Matthew Beaumont’s recent book Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London, who shaped how we imagine the urban night and ‘helped define the condition of social displacement and spiritual homelessness that is central to our understanding of the everyday experience of capitalist modernity’. If that sounds too dryly academic, just look at my transcription of the opening of Night in the City (also later made into a film for BBC television, in 1957).

ACTUALITY: (church bells and footsteps)

[Prostitute’s voice:] You’re walking along the streets and you’re seeing all the lights on and you’re just wishing to yourself “Oh, if only I could get in there” y’know. You’re walking about all night looking at things.

(up footsteps and fade under)

ANNOUNCER: Night in the city. It’s deserted and cold. But on the brick croft, round the watchman’s fire, in the shadows of the warehouse, there are people talking. People caught up in the restlessness and loneliness of the city night.

(footsteps and policeman whistling ‘Dirty Old Town’)

MITCHELL: Past midnight. Time to explore the city. This symbol of art and order. This beehive. Explore, for it’s no longer workaday and familiar; it’s an unknown land. A poultice of silence has been spread over it. Silence and shadow have transformed it, and have wrapped mystery and menace and beauty around the shabby warehouse, and croft and dock and bombsite and canal and shunting-yard. (‘Dirty Old Town’ theme – sung by Ewan MacColl with guitar by Fitzroy Coleman)

- Mitchell is known for his impressionistic documentaries, but he was equally adept at reportage or investigative journalism.

As we have seen from the above extract from Night in the City, Mitchell was skilled as a script-writer. (Incidentally, it has also been claimed by a reputable source that he wrote some of the lyrics to Dirty Old Town!) However, he generally preferred to dispense with a script altogether, creating instead the nucleus of a radio programme or film soundtrack by editing together extracts from dozens of hours of tape recordings. The impressionistic, ‘stream of consciousness’ style that resulted from this modus operandi meant that Mitchell was rightly referred to as a poet or artist of the documentary form. However, it is arguable that Mitchell’s work in radio was also a continuation of that journalistic tradition of social investigation exemplified by the early Manchester Guardian:

The Guardian was no longer confining itself, as it had tended to do, to reporting what public men said and commenting on it, or to describing events which happened in the public eye or led to actions in the courts. It was itself making news out of the hidden occurrences of ordinary life, bringing out dark things, which the enlightened conscience of middle and upper class England ought to have known, but did not. (Tremayne 1995: 33)

Mitchell befriended and collaborated with several Guardian journalists during his time at BBC Manchester, and in 1953 he co-scripted and co-narrated a remarkable radio programme with a Canadian journalist, Patrick Keatley. Entitled Horses Can’t Talk, it was an investigation into the cruelties involved in the transport, sale, slaughter, and human consumption of horses. Keatley had published several articles on the subject in the Manchester Guardian. As a result of these shocking articles, the Royal Commission had been appointed to investigate horse slaughter.

Mitchell and Keatley’s powerful programme featured not only actuality of slaughterers, dealers and veterinary surgeons, but the ‘bona fide’ recording of the agonised drumming of hooves by a pony whose slaughterer had failed to put him down at the first shot. As might be expected, it was a controversial programme, receiving much comment from the listening public, various organizations concerned with animal welfare or trade, and polarised responses from Members of Parliament. In fact, questions were asked about the programme in the House of Commons, and a motion of censure on the BBC was actually tabled (but not debated), which stated that an allegation of cruelty in the slaughter of horses was in conflict with the Committee of Inquiry!

This topic has renewed relevance and topicality, due to the recent (2013) horsemeat scandal. Shockingly, Mitchell and Keatley interviewed a trader in their programme who asserted that electrical pumps were being used to drain blood from live horses, in the preparation of horsemeat which was then being sold as veal. Plus ça change.

Another interesting aspect was the inclusion of a remarkable short sequence in the middle of the programme, in which we hear a recording of a production meeting in which Mitchell and Keatley argue – politely but firmly – over editorial and ethical decisions in how to report the slaughter of horses. Mitchell accuses Keatley of ‘colouring the issue’ by writing about a frightened pony ‘waiting for death’, questioning his presumption of a horse’s sentience. As Mitchell noted in a BBC memo, ‘We hold rather dissimilar views and draw rather different conclusions from the evidence we produce on record, and this will be reflected in the narration.’ The decision to include this sequence was bold and original, and introduces a clever self-reflexive element to what might otherwise be seen as fairly ‘straight’ reportage.

Throughout his career, Mitchell was to confound those people who tended to ‘pigeon-hole’ him for his use of the impressionistic ‘think-tape’ technique about working class subjects by creating gritty observational (‘fly-on-the-wall’) documentaries or current affairs documentaries, for example, for Granada Television’s World in Action. Horses Can’t Talk was an example of Mitchell not as ‘auteur’ (as he was subsequently cast) but as the “dryly monosyllabic journalist” described by his contemporary Philip Donnellan and colleague Norman Swallow (“no interviewer has extracted more by saying less”).

The very calm, avuncular and ‘cosy’ image we have of him from the few filmed interviews that exist belies the fact that Mitchell was wildly energetic and prolific throughout his career. He was seemingly making up for lost time, having started work in British broadcasting – he had previously worked for the South African Broadcasting Corporation – relatively late in life, at the age of 38. On 3rd April 1949 the South African Sunday Express ran a story about Mitchell which began as follows:

When a radio producer fell asleep over his restaurant meal in Johannesburg two nights ago, only the members of his party knew the reason – he had completed 32 ½ hours without a break arranging the radio programme Our Country, which ran for an hour, and which featured 140 interviewees. He is Denis Mitchell, and it was his last programme for the S.A.B.C. He intends trying his luck in Britain.

Denis Mitchell in Africa, during the making of Rhodesian Journey, 1953. Courtesy of Betty Mitchell.

In 1986 Frank Shaw wrote an account of assisting Mitchell both with the radio programme The Talking Streets and its television ‘adaptation’ Morning in the Streets in 1958-9:

He lugged the heavy recorder himself. I filled the big pockets of my overcoat with tapes. I took him to people – in pubs, shops, pensioner’s clubs, youth clubs, council offices, round the docks, up back streets, to churches, police stations, drinking clubs, parks, garden suburbs, wash houses, on the docks, bobbies, priests, publicans, do-gooders, criminals, boxers, dockers … We worked a ten hour day, drinking while we worked, snatching meals anyhow – in taxis until the drivers objected to the smell of chips. This meant half-a-dozen or so tapes a day, each containing an hour. He did cutting at night time…

There are sixty full seconds to a minute with Denis Mitchell. (Shaw 1986)

- Finally, Mitchell had a generosity of spirit which he meant that he never claimed or received his due credit for inspiring other works.

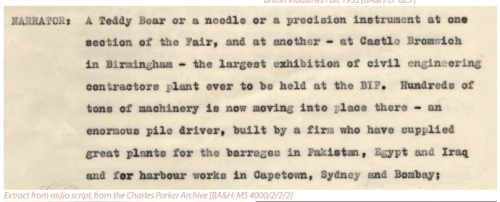

As is often the fate of the pioneer, Mitchell developed original ideas and approaches which were then taken up by others and no credit given to the original progenitor. Mitchell’s influence on the MacColl/Parker/Seeger Radio Ballads was rightly acknowledged by Gillian Reynolds in the recent People Talking programme. The exact nature and extent of the influence may never be known, and certainly deserves further research. However, there are some key connections. Firstly, Mitchell had worked extensively with Ewan MacColl at BBC Manchester from c. 1953 to c. 1957 (see below), and also sometime during the mid-1950s spent some time in Birmingham giving training to staff at the BBC Midland Region, including Charles Parker. During this time Mitchell scripted a radio feature produced by Parker about the British Industries Fair at Castle Vale.

Courtesy of Birmingham Archives & Heritage.

Mitchell and MacColl collaborated for the first time on a radio feature called Lorry Harbour. Broadcast on Friday 4th January 1952, it portrayed the life of long distance lorry drivers who travel the ‘trunk’ roads and stop at all-night transport cafes, and MacColl wrote ‘Champion at Keeping Them Rolling’ and ’21 Years’ for the programme (which were to enter into the trucker repertoire).

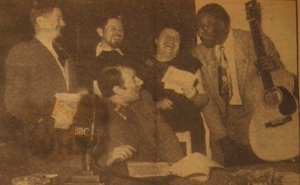

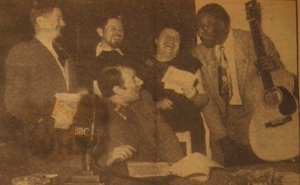

In 1953 Mitchell commissioned MacColl to write folk songs that acted as linking narration for a feature called The Railway King about George Hudson, and thereby build up a portrait of Hudson as what Mitchell termed a ‘folk-character’. That same year Mitchell again secured the services of Ewan MacColl as a scriptwriter and narrator, for the six-part series Ballads and Blues (1953) about the roots of folk music, which showcased British and American folk, blues and jazz. This series – which was divided into themes such as love, war, the railways, the sea – featured the cream of British and American folk talent, and introduced MacColl to a gallery of musicians and contacts he’d use over the next 20 years, including future Radio Ballad regulars like A. L. (Bert) Lloyd and Seamus Ennis. Both The Railway King and Ballads and Blues clearly prefigure the Radio Ballads.

From L-R: Denis Mitchell, Ewan MacColl, Neva Raphaello, Big Bill Broonzy and (seated) Humphrey Lyttleton. During the production of ‘Song of the Iron Road’ for the Ballads and Blues series, Broadcasting House, 1955.

In later interviews and recorded recollections, however, Ewan MacColl minimised or entirely ‘wrote out of history’ the pivotal role of Denis Mitchell in creating these programmes. (For example, in the recent (2014) book of interviews Legacies of Ewan MacColl MacColl discusses The Railway King and Ballads and Blues as programmes devised and written by himself and Bert Lloyd). In bringing some of the ideas and techniques he had earlier developed in collaboration with Mitchell into the Radio Ballads, MacColl was undoubtedly emboldened by Mitchell’s move into television, and also his growing contempt for what he regarded as the ‘selling out’ of his increasingly successful (and largely apolitical) former friend, collaborator and Manchester neighbour.

As important and magical as the Radio Ballads were, they were often too densely packed with speech and song, and what they were arguably lacking was Mitchell’s skill at ironic juxtaposition and the creation of uncluttered and evocative soundscapes.

Conclusion

I’m now hoping that the recent radio programme, and a current British Film Institute project to showcase classic television documentaries of the 1950s and 1960s (watch this space!), will restore some critical attention to the work of Denis Mitchell in both radio and television. There are many fascinating bye-ways in Mitchell’s career – for example, the ‘double biography’ of Quentin Crisp and Philip O’Connor by Andrew Barrow (2004) gives an interesting and kaleidoscopic perspective and ‘back story’ on Mitchell’s film profile of Crisp for World in Action (1970) and film collaboration with O’Connor The Changing Village (BBC, 1962); Mitchell’s relationship with Crisp; and the author’s own relationship with Mitchell.

I’ll finish by including here a letter sent to Mitchell by the comedian Spike Milligan in 1959.

Denis Mitchell Esq.

BBC Television Centre

London W12

Dear Denis Mitchell,

I always keep my television in the toilet because most of the subject matter is best fitted to that little precinct.

I must tell you that your ‘Soho Story’ was magnificent, one of the most marvellous pieces of television to date. I think that’s about all.

Sincerely,

Spike Milligan

P.S. How did you manage to get it past your idiot hierarchy? (Milligan 2013)

© Ieuan Franklin, 2015.

References

Newspaper sources (South African Daily Express and picture of ‘Ballads and Blues’ production) courtesy of Linda Mitchell.

Photographs courtesy of Betty Mitchell.

Archival sources:

Various files at BBC Written Archives at Caversham, including:

BBC WAC North Region, Features, People Talking, Unusual Beliefs, N2/96

BBC WAC North Region, Features, Horses Can’t Talk, N2/51.

BBC WAC North Region, Features, Lorry Harbour, N2/65.

Published sources:

Barrow, A. (2004). Quentin and Philip: A Double Portrait, (London: Pan).

Beaumont, M. (2015). ‘Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London, (London: Verso).

Darlow, M. (1990). ‘Denis Mitchell 1st August 1911 – 1st October 1990. A Celebration of his Life and Work’ (National Film Theatre Programme, London), unpaginated.

McCartney, A. (1995). “The Ambiguous Relation.” Contact! 9(1).

Milligan, S. (2013). Spike Milligan: Man of Letters, (London: Viking).

Reisz, K. (1959). ‘On The Outside Looking In: Denis Mitchell’s Television Films’, in Whitebait, W. (ed.) (1959), International Film Annual No. 3, (London: John Calder).

Shaw, F. (1986). My Liverpool, (Liverpool: Gallery Press).

Tremayne, C. (1995). “Made in Manchester.” British Journalism Review 6(3): 33-37.